The Cambodian Civil War was a conflict that pitted the forces of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (known as the Khmer Rouge) and their allies the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) and the Viet Cong against the government forces of Cambodia (after October 1970, the Khmer Republic), which were supported by the United States (U.S.) and the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam).

The struggle was exacerbated by the influence and actions of the allies of the two warring sides. People's Army of Vietnam (North Vietnamese Army) involvement was designed to protect its Base Areas and sanctuaries in eastern Cambodia, without which the prosecution of its military effort in South Vietnam would have been more difficult. Then following the Cambodian coup of 1970, the North Vietnamese Army's attempt to overrun the entire country in March–April 1970 plunged Cambodia into civil war.[4] The U.S. was motivated by the desire to buy time for its withdrawal from Southeast Asia, to protect its ally in South Vietnam, and to prevent the spread of communism to Cambodia. American and both South and North Vietnamese forces directly participated (at one time or another) in the fighting. The central government was mainly assisted by the application of massive U.S. aerial bombing campaigns and direct material and financial aid.

After five years of savage fighting, the Republican government was defeated on 17 April 1975 when the victorious Khmer Rouge proclaimed the establishment of Democratic Kampuchea. Thus, it has been argued that the US intervention in Cambodia contributed to the eventual seizure of power by the Khmer Rouge, that grew from 14,000 in number in 1970 to 70,000 in 1975.[5] This view has been disputed,[6][7][8] with documents uncovered from the Soviet archives revealing that the North Vietnamese invasion of 1970 was launched at the explicit request of the Khmer Rouge following negotiations with Nuon Chea.[4] It has also been argued that US bombing was decisive in delaying a Khmer Rouge victory.[9][10][11][12]

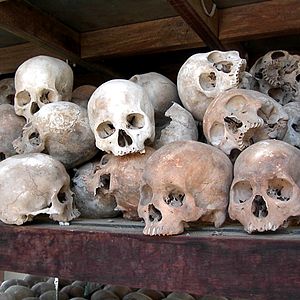

The conflict, although an indigenous civil war, was considered to be part of the larger Vietnam War (1959–1975) that also consumed the neighboring Kingdom of Laos, South Vietnam, and North Vietnam. This civil war led to the Cambodian Genocide, one of the bloodiest in history.

Revolt in Battambang

The prince then found himself in a political dilemma. To maintain the balance against the rising tide of the conservatives, he named the leaders of the very group he had been oppressing as members of a "counter-government" that was meant to monitor and criticize Lon Nol's administration.[22] One of Lon Nol's first priorities was to fix the ailing economy by halting the illegal sale of rice to the communists. Soldiers were dispatched to the rice-growing areas to forcibly collect the harvests at gunpoint, and they paid only the low government price. There was widespread unrest, especially in rice-rich Battambang Province, an area long-noted for the presence of large landowners, great disparity in wealth, and where the communists still had some influence.[23][24] On 11 March 1967, while Sihanouk was out of the country in France, a rebellion broke out in the area around Samlaut in Battambang, when enraged villagers attacked a tax collection brigade.

With the probable encouragement of local communist cadres, the insurrection quickly spread throughout the whole region.[25] Lon Nol, acting in the prince's absence (but with his approval), responded by declaring martial law.[22] Hundreds of peasants were killed and whole villages were laid waste during the repression.[26] After returning home in March, Sihanouk abandoned his centrist position and personally ordered the arrest of Khieu Samphan, Hou Yuon, and Hu Nim, the leaders of the "counter government", all of whom escaped into the northeast.[27]

Simultaneously, Sihanouk ordered the arrest of Chinese middlemen involved in the illegal rice trade, thereby raising government revenues and placating the conservatives. Lon Nol was forced to resign, and, in a typical move, the prince named new leftists to the government to balance the conservatives.[27] The immediate crisis had passed, but it engendered two tragic consequences. First, it drove thousands of new recruits into the arms of the hard-line maquis of the Cambodian Communist Party (which Sihanouk labelled the Khmer Rouge or "Red Khmers"). Second, for the peasantry, the name of Lon Nol became associated with ruthless repression throughout Cambodia.[28]

Communist regroupment

For more details on this topic, see Khmer Rouge.

While the 1967 insurgency had been unplanned, the Khmer Rouge tried, without much success, to organize a more serious revolt during the following year. The prince's decimation of the Prachea Chon and the urban communists had, however, cleared the field of competition for Saloth Sar (also known as Pol Pot), Ieng Sary, and Son Sen—the Maoist leadership of the maquisards.[29] They led their followers into the highlands of the northeast and into the lands of the Khmer Loeu, a primitive people who were hostile to both the lowland Khmers and the central government. For the Khmer Rouge, who still lacked assistance from the North Vietnamese, it was a period of regroupment, organization, and training. Hanoi basically ignored its Chinese-sponsored allies, and the indifference of their "fraternal comrades" to their insurgency between 1967 and 1969 would make an indelible impression on the Khmer Rouge leadership.[30][31]

On 17 January 1968, the Khmer Rouge launched their first offensive. It was aimed more at gathering weapons and spreading propaganda than in seizing territory since, at that time, the adherents of the insurgency numbered no more than 4–5,000.[32][33] During the same month, the communists established the Revolutionary Army of Kampuchea as the military wing of the party. As early as the end of the Battambang revolt, Sihanouk had begun to reevaluate his relationship with the communists.[34] His earlier agreement with the Chinese had availed him nothing.

They had not only failed to restrain the North Vietnamese, but they had actually involved themselves (through the Khmer Rouge) in active subversion within his country.[25] At the suggestion of Lon Nol (who had returned to the cabinet as defense minister in November 1968) and other conservative politicians, on 11 May 1969, the prince welcomed the restoration of normal diplomatic relations with the U.S. and created a new Government of National Salvation with Lon Nol as his prime minister.[35] He did so "in order to play a new card, since the Asian communists are already attacking us before the end of the Vietnam War."[36] Besides, PAVN and the NLF would made very convenient scapegoats for Cambodia's ills, much more so than the minuscule Khmer Rouge, and ridding Cambodia of their presence would solve many problems simultaneously.[37] The Americans took advantage of this same opportunity to solve some of their own problems in Southeast Asia.

Operation Menu

For more details on the bombing campaign, see Operation Menu.

Although the U.S. had been aware of the PAVN/NLF sanctuaries in Cambodia since 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson had chosen not to attack them due to possible international repercussions and his belief that Sihanouk could be convinced to alter his policies.[38] Johnson did, however, authorize the reconnaissance teams of the highly classified Military Assistance Command, Vietnam Studies and Observations Group (SOG) to enter Cambodia and gather intelligence on the Base Areas in 1967.[39] The election of Richard M. Nixon in 1968 and the introduction of his policies of gradual U.S. withdrawal from South Vietnam and the Vietnamization of the conflict there, changed everything. On 18 March 1969, on secret orders from Nixon, the U.S. Air Force carried out the bombing of Base Area 353 (in the Fishhook region opposite South Vietnam's Tay Ninh Province) by 59 B-52 Stratofortress bombers. This strike was the first in a series of attacks on the sanctuaries that lasted until May 1970. During Operation Menu, the Air Force conducted 3,875 sorties and dropped more than 108,000 tons of ordnance on the eastern border areas.[40] During this operation, Sihanouk remained quiet about the whole affair, possibly hoping that the U.S. would be able to drive PAVN and NLF troops from his country. Hanoi too, remained quiet, not wishing to advertise the presence of its forces in "neutral" Cambodia. Only five high-ranking Congressional officials were informed of the bombing.

Overthrow of Sihanouk (1970)

Lon Nol coup

For more details on this topic, see Cambodian coup of 1970.

While Sihanouk was out of the country on a trip to France, anti-Vietnamese rioting (which was semi-sponsored by the government) took place in Phnom Penh, during which the North Vietnamese and NLF embassies were sacked.[41][42] In the prince's absence, Lon Nol did nothing to halt these activities.[43] On 12th, the prime minister closed the port of Sihanoukville to the North Vietnamese and issued an impossible ultimatum to them. All PAVN/NLF forces were to withdraw from Cambodian soil within 72 hours (on 15 March) or face military action.[44]

Sihanouk, hearing of the turmoil, headed for Moscow and Beijing in order to demand that the patrons of PAVN and the NLF exert more control over their clients.[35] On 18 March 1970, Lon Nol requested that the National Assembly vote on the future of the prince's leadership of the nation. Sihanouk was ousted from power by a vote of 92–0.[45] Heng Cheng became president of the National Assembly, while Prime Minister Lon Nol was granted emergency powers. Sirik Matak retained his post as deputy prime minister. The new government emphasized that the transfer of power had been totally legal and constitutional, and it received the recognition of most foreign governments. There have been, and continue to be, accusations that the U.S. government played some role in the overthrow of Sihanouk, but conclusive evidence has never been found to support them.[46]

The majority of middle-class and educated Khmers had grown weary of the prince and welcomed the change of government.[47] They were joined by the military, for whom the prospect of the return of American military and financial aid was a cause for celebration.[48] Within days of his deposition, Sihanouk, now in Beijing, broadcast an appeal to the people to resist the usurpers.[35] Demonstrations and riots occurred (mainly in areas contiguous to PAVN/NLF controlled areas), but no nationwide groundswell threatened the government.[49] In one incident at Kompong Cham on 29 March, however, an enraged crowd killed Lon Nol's brother, Lon Nil, tore out his liver, and cooked and ate it.[48] An estimated 40,000 peasants then began to march on the capital to demand Sihanouk's reinstatement. They were dispersed, with many casualties, by contingents of the armed forces.

Massacre of the Vietnamese

Most of the population, urban and rural, took out their anger and frustrations on the nation's Vietnamese population. Lon Nol's call for 10,000 volunteers to boost the manpower of Cambodia's poorly equipped, 30,000-man army, managed to swamp the military with over 70,000 recruits.[50] Rumours abounded concerning a possible PAVN offensive aimed at Phnom Penh itself. Paranoia flourished and this set off a violent reaction against the nation's 400,000 ethnic Vietnamese.[48]

Lon Nol hoped to use the Vietnamese as hostages against PAVN/NLF activities, and the military set about rounding them up into detention camps.[48] That was when the killing began. In towns and villages all over Cambodia, soldiers and civilians sought out their Vietnamese neighbors in order to murder them.[51] On 15 April, the bodies of 800 Vietnamese floated down the Mekong River and into South Vietnam.

The South Vietnamese, North Vietnamese, and the NLF harshly denounced these horrendous actions.[52] Significantly, no Cambodians—not even those of the Buddhist community—condemned the killings. In his apology to the Saigon government, Lon Nol stated that "it was difficult to distinguish between Vietnamese citizens who were Viet Cong and those who were not. So it is quite normal that the reaction of Cambodian troops, who feel themselves betrayed, is difficult to control."[53]

NUFK and RGNUK

From Beijing, Sihanouk proclaimed that the government in Phnom Penh was dissolved and his intention to create the Front Uni National du Kampuchea or NUFK (National United Front of Kampuchea). Sihanouk later said "I had chosen not to be with either the Americans or the communists, because I considered that there were two dangers, American imperialism and Asian communism. It was Lon Nol who obliged me to choose between them."[48]

The North Vietnamese reacted to the political changes in Cambodia by sending Premier Phạm Văn Đồng to meet Sihanouk in China and recruit him into an alliance with the Khmer Rouge. Saloth was also contacted by the Vietnamese who now offered him whatever resources he wanted for his insurgency against the Cambodian government. Saloth and Sihanouk were actually in Beijing at the same time but the Vietnamese and Chinese leaders never informed Sihanouk of the presence of Saloth or allowed the two men to meet. Shortly after, Sihanouk issued an appeal by radio to the people of Cambodia to rise up against the government and support the Khmer Rouge. In doing so, Sihanouk lent his name and popularity in the rural areas of Cambodia to a movement over which he had little control.[54] In May 1970, Saloth finally returned to Cambodia and the pace of the insurgency greatly increased. After Sihanouk showed his support for the Khmer Rouge by visiting them in the field, their ranks swelled from 6,000 to 50,000 fighters.

The prince then allied himself with the Khmer Rouge, the North Vietnamese, the Laotian Pathet Lao, and the NLF, throwing his personal prestige behind the communists. On 5 May, the actual establishment of NUFK and of the Gouvernement Royal d'Union Nationale du Kampuchea or RGNUK (Royal Government of National Union of Kampuchea), was proclaimed. Sihanouk assumed the post of head of state, appointing Penn Nouth, one of his most loyal supporters, as prime minister.[48]

Khieu Samphan was designated deputy prime minister, minister of defense, and commander in chief of the RGNUK armed forces (though actual military operations were directed by Pol Pot). Hu Nim became minister of information, and Hou Yuon assumed multiple responsibilities as minister of the interior, communal reforms, and cooperatives. RGNUK claimed that it was not a government-in-exile since Khieu Samphan and the insurgents remained inside Cambodia. Sihanouk and his loyalists remained in China, although the prince did make a visit to the "liberated areas" of Cambodia, including Angkor Wat, in March 1973. These visits were used mainly for propaganda purposes and had no real influence on political affairs.[55]

For Sihanouk, this proved to be a short-sighted marriage of convenience that was spurred on by his thirst for revenge against those who had betrayed him.[56][57] For the Khmer Rouge, it was a means to greatly expand the appeal of their movement. Peasants, motivated by loyalty to the monarchy, gradually rallied to the NUFK cause.[58] The personal appeal of Sihanouk, and widespread US aerial bombardment helped recruitment. This task was made even easier for the communists after 9 October 1970, when Lon Nol abolished the loosely federalist monarchy and proclaimed the establishment of a centralized Khmer Republic.[59